Behind the security bars of a spartan, white-tiled room, 25 youths are arranging bedrolls on the floor. The workers on the Salvation Army nightshift, who watch over these lone foreign teenagers in a shelter in a gritty corner of Paris, are distributing sheets and sleeping bags; there are a couple of boys from Mali and a contingent of Bangladeshis; the rest have travelled overland, by every conceivable method, from Afghanistan.

The youngest are 13 years old, pint-sized cousins from Kabul who arrived that morning after a journey of five months. They take off their trainers and place them at the end of their bedrolls. One of them, Morteza, gingerly peels off his socks. The undersides of his toes are completely white.

I ask what happened to his feet. "Water," he says. Where was he walking in water? Mohammed, the boy on the next bedroll who knows more English, translates. "In the mountains," he says. Which mountains, I ask, thinking about the range that forms the border between Turkey and Iran. "Croatia, Slovenia, Italy,'' Morteza says. Mohammed intervenes. "Not water,'' he clarifies. "Snow."

Suddenly I understand. Morteza's feet are not waterlogged or blistered. He has limped across Europe with frostbite.

The next day I run into them watching the older Afghans play football in a park. Morteza's 13-year-old cousin Sohrab, pale and serious beyond his years, recounts, in English learned during two years of school in Afghanistan, what happened. "Slovenia big problem,'' he says, explaining how he and Morteza, "my uncle's boy'', were travelling with eight adults when they were intercepted by the Slovenian police. Two members of their group were caught and the rest made a detour into the mountains. They spent five days in the snow, navigating by handheld GPS, emerging from the Alps in Trento, in the Italian north.

The road to peace: 13-year-old Morteza spent five months travelling from Kabul to Paris. His journey took him through Iran, Turkey, Greece, Macedonia, Serbia, Croatia, Slovenia and Italy Photograph: Ed Alcock/MYOP

The road to peace: 13-year-old Morteza spent five months travelling from Kabul to Paris. His journey took him through Iran, Turkey, Greece, Macedonia, Serbia, Croatia, Slovenia and Italy Photograph: Ed Alcock/MYOP Morteza acquired frostbite on the penultimate part of a 6,000km journey that detoured through the Balkans: through Macedonia, Serbia and Croatia. Their aim is to join their uncle who lives in Europe, the solution their relatives found after Morteza's father was killed in an explosion. His mother died earlier "in the war''; Sohrab lost his own father when he was 11.

Morteza and Sohrab are among the world's most vulnerable migrants. Like scores of Afghan teenagers in transit across Europe, they are in flight from violence or the aftershocks of violence that affect children in particularly harsh ways. Those who turn up in Paris have spent up to a year on the road, on the same clandestine routes as adults, but at far greater risk.

No one knows how many unaccompanied Afghan children have made it to Europe. Paris took in just over 300 in 2011 – the biggest nationality among the 1,700 lone foreign minors in its care. Sarah Di Giglio, a child-protection expert with Save the Children in Italy, says that last year the number of Afghan boys – there are almost never girls – passing through a day centre in Rome had doubled from the year before, to 635.

Asylum statistics are another measure, though they give only a rough indication since many children never make a claim. Still, at 4,883, Afghans were the biggest group of separated foreign children requesting asylum in 2010, the majority in Europe.

While some are sent out of Afghanistan for their own safety, others make their own decision to leave. Some are running from brutality, or the politics of their fathers, or recruitment by the Taliban. Others have been pushed onwards by the increasing precariousness of life in Pakistan and Iran, countries that host three million Afghan refugees.

Blanche Tax, who is responsible for country guidance at the United Nations refugee agency in Geneva, says security is deteriorating in Afghanistan, which Unicef described two years ago as the world's most dangerous place to be a child. From January to September, she said, 1,600 children were reported killed or injured, 55% more than the previous year.

A report to the general assembly of the UN security council on 13 December 2011, meanwhile, said "the killing and maiming of children remains of grave concern". "The most frequent violations continued to be recruitment and use of children, including for suicide bombing missions or for planting explosives,'' the report continued. It highlighted a recent rise in "cross-border recruitment by Taliban – as well as attacks on schools''. And it added 31,385 cases of "severe acute malnutrition" among minors to a litany of child-specific damage that already includes landmines, sexual violence and forced labour.

It is from this maelstrom, and its spread to Afghanistan's south, north and east, that Morteza, Sohrab and others have fled. I first came across adolescents like them three years ago, when I saw them squeezing between the railings of a Paris park to sleep on cardboard among the shrubberies or in the bandstand, along with adult refugees. When the police raided the park and started to patrol it with dogs, they bedded down under the swings of a playground, or on the edges of a canal.

Subsequent raids have moved them on again, but they still play football there or under a railway bridge, in teams that sometimes take on the local boys. They find the undersized Salvation Army shelter by word of mouth, or through a reception office for unaccompanied foreign minors run by a French NGO called France Terre d'Asile (FTDA). It's the only emergency place of refuge for the children, and is oversubscribed: lately 20 or so have been turned away each evening, to sleep in a corner of a park or metro station, or walk the streets all night in order to keep warm.

Omar, 16, was separated from his father while fleeing Afghanistan Photograph: Ed Alcock/MYOP

Omar, 16, was separated from his father while fleeing Afghanistan Photograph: Ed Alcock/MYOP In the entrance to the FTDA office for minors I stumble upon Omar, a slender 16-year-old with a ski hat pulled low over his eyes. He is leaning on the counter by himself, too tense to wait on the seats with the other boys. He is doodling with a yellow marker pen on a sheet of paper on which someone before him has pencilled the word "Tunisia".

"All my family are very worried about my father,'' Omar says. "We don't know where he is.'' This is almost the first thing he tells me. He expresses this same anxiety four times in our conversation, and I realise that what initially I took for tension was distress.

From a village in Afghanistan's Logar province, just south of Kabul, Omar says he is the eldest of five. Enmities from the Soviet era up-ended his life. "I did school in Afghanistan for three years and I wasn't able to go more,'' he said. "My grandfather said don't go to school, we have enemies who will kill you; stay in the house and don't go out in the village a lot." His father and grandfather had "done jihad with the Russians", he said; those they had sided against came back and "gave a warning". His grandfather sold their almond orchard and paid $11,000 to a smuggler to get him and his father out.

Travelling with Omar's uncle, the three made it as far as Turkey before being stopped by the police. Everyone scattered. Separated in the confusion, Omar was deported to Afghanistan. He said his uncle had contacted his grandfather to let them know he was all right; from his father they have had no word.

Omar set off again, spending the next five months on the road. He moved in and out of the hands of smugglers, was held with dozens of others in "passenger houses'', then abandoned in a deserted place on the Turkish side of the border with Greece. There, he and his companions waited, night after night without shelter, for a guide. Finally they gave up and struggled back to Istanbul.

On his second attempt Omar swam a wide canal and walked for five hours in wet clothes, heading on his smuggler's instructions towards the lights of a Greek town. There he was picked up by the police and held for three days in a room with 15 men. The next four nights he spent in a train station in the northern Greek town of Alexandroupolis, until a railway employee paid his fare to Athens. He waited 25 days in another passenger room before being crammed, with 32 others, into the back of a truck. Told to bring two packets of biscuits and no water, they spent 30 hours inside. "There was no air and it smelt very bad," he said. The driver abandoned them in Italy.

He caught trains to Milan, and then Cannes, with three other boys. "We slept on the earth next to the sea and we were so cold," he says. Arriving in Paris, he spent six nights on the street before asking at this office for help. "I want to live here,'' he says. "People don't hurt me in France." And yet, they already had. A few days earlier three men had mugged him in a Paris park. They stole his bag that contained his last €30 and the slip of paper that bore his grandfather's phone number, severing his last link to his family.

In the state of anxiety he was in, it was hard for him to think about the future. "I want to have peace,'' he said. And if he were able to stay in France? "I'd like to go to school,'' he said, "if they give us the opportunity to go." For many of the kids going to school seems like an enormous privilege, but first they have to be accepted as minors. That means going before a judge, who can order bone x-ray exams – which have a two-year margin of error – if he disbelieves their age; they may have to wait months to get formal protection.

Waiting in hope: boys from Afghanistan, Pakistan, Bangladesh and sub-Saharan Africa line up in the hope of being offered a bed for the night Photograph: Ed Alcock/MYOP

Waiting in hope: boys from Afghanistan, Pakistan, Bangladesh and sub-Saharan Africa line up in the hope of being offered a bed for the night Photograph: Ed Alcock/MYOP By the time they turn 18, these teenagers will have to prove they speak French and have embarked on a profession in order to have a chance of regularising their status. For Afghan boys with almost no prior schooling, the pressure is enormous. "They have no time to have their adolescent crises,'' says Pauline Ferrais, head of the education service at the Maison du Jeune Réfugié (MJR), a day centre. As Pierre Henry, managing director of FTDA, puts it: "Some have spent one or two years on the roads of Asia and Europe in extreme conditions playing with the laws of survival, and we ask them to respect very strict rules in an education system that makes no allowances for them." Yet teachers remark that those who do go to school have a dynamic effect on the class. It's something that's been noted by Romain Levy, the deputy mayor for Paris with special responsibility for minors. "Because of their motivation they act as an engine and pull the other kids up," he says.

But Paris's budget for providing for minors is stretched. And elsewhere in Europe the likelihood that these boys will get a second chance at a childhood is waning. Sweden, alarmed by the 1,693 Afghan teenagers who requested asylum there in 2011, has teamed up with Britain, Norway and the Netherlands to create the European Return Platform for Unaccompanied Minors, or Erpum, an EU-funded project that aims to send them back.

Susanne Bäckstedt, its Stockholm-based co-ordinator, denied reports that Erpum wanted to establish care centres in Kabul. She said the programme would be voluntary, and only involve minors who had exhausted asylum appeals and wanted to rejoin their families. "We are not discussing care centres,'' says Bäckstedt. "We will only send them back if their family can be traced.'' That, she says, meant "a welcoming family'' who would come to the airport to meet them.

Erpum hopes to start repatriations of 16- and 17-year-olds this year, provided the Afghan Ministry of Refugees and Repatriation agrees; Bäckstedt confirmed Erpum has a target of deporting 100 Afghan minors by the end of 2014. The prospect has alarmed child-protection bodies, who fear such initiatives will push those in Europe underground. They want reassurances over how the minor's best interest would be established, stress the danger to the tracers of inaccurate information, and warn that families who have spent thousands of dollars to send a son to safety will have incurred debts in which collateral can include the betrothal of a younger sister to an older man. "Family tracing is not as innocent as it sounds," says one children's rights researcher. The European Council on Refugees and Exiles also opposes returning minors to Afghanistan.

Governments concerned about deterring minors from embarking on hazardous journeys risk missing the point about why children flee in the first place, says Judith Dennis, policy adviser at the UK Refugee Council. "We share concerns that children's journeys to safety are often dangerous,'' she comments, "but it is inappropriate to suggest that the international response should be to discourage them from escaping the threats in their country.''

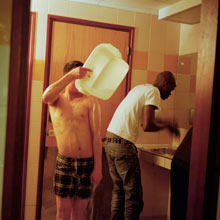

Young refugees at the Maison du Jeune Réfugié, trying to reorientate themselves after the long journey to Paris. Photograph: Ed Alcock/MYOP

Young refugees at the Maison du Jeune Réfugié, trying to reorientate themselves after the long journey to Paris. Photograph: Ed Alcock/MYOP Every Afghan minor who has survived the endurance test that reaching Europe entails has a story of equal parts courage and grief. Some of them are too frightened, or too traumatised, or simply too young to be able to explain the forces that have borne them here.

I meet Jalil, a round-faced 16-year-old from Kunduz, in Afghanistan's north, between classes at the MJR, where he is taught French. "This is my first school,'' he says with pride. His only education hitherto had been from a neighbour in Afghanistan who came to his house at night to teach him English, "one word at a time", from a book.

Jalil took his future into his own hands after being orphaned. He had lost his mother to "a heart sickness" when he was nine or 10 and was living with his father, who was killed "three years and four months ago". "Someone said he helped the Taliban," Jalil tells me. He didn't witness the attack. "But my brother saw that and now he is mad,'' Jalil says. "He can't talk. It is like he is finished. He is 22 years old.''

Young refugees at the Maison du Jeune Réfugié. Photograph: Ed Alcock/MYOP

Young refugees at the Maison du Jeune Réfugié. Photograph: Ed Alcock/MYOP He and his younger siblings moved to his uncle's house, where he was often beaten. "He was cruel, cruel, cruel," Jalil says of his uncle. His brother-in-law helped him get away, paying $4,000 to a smuggler to get him to Turkey. Barely 15, he went first to Pakistan, then Iran, and on to Turkey and Greece. He had no money so he stayed there "a long time", living by washing windows, then crossed into Italy from the Greek port of Patras by clinging to the chassis of a truck. After a nine-month journey he reached Paris in August, and slept for a month in the street. Now he is learning the language and goes every day after class to "the library with headphones" at the Pompidou Centre. "I go there and listen to French," he says. "The plan is I study more to be a doctor, but if I cannot do a big job I will do a little job. If I can't be a doctor I will be an electrician.''

Pierre Henry of FTDA believes that Europe should be investing in these teenagers. "You don't win war, democracy, hearts with occupying armies,'' he says, pointing out that educating these minors would help create the diaspora that will one day rebuild their country. "It puts paid to all our values if we can't take care of those among the world's disinherited children who come to us."

A week later I pass by the meeting point where the new arrivals gather to be chosen for the 25 places in the Salvation Army shelter. Forty-five boys are waiting in a ragtaggle line against a supermarket wall, and every one of them is new. Sohrab and Morteza, the boy with frostbitten feet, have left; they are back on the road. There is no sign of Omar. Jalil, who lined up here four months ago, now has a place in a hotel, though sometimes he stops by a nearby soup kitchen, where many Afghans gather, to speak his language again. The others have disappeared on their search across Europe for some place that will allow them to stay. They leave only their stories behind.

Hinterland, a novel by Caroline Brothers about Afghan boys in Europe, is published on 2 February by Bloomsbury, £14.99. To order a copy for £11.99 with free UK p&p, go to guardian.co.uk/bookshop or call 0330 333 6846

No comments:

Post a Comment